The Science of Shelterbelts

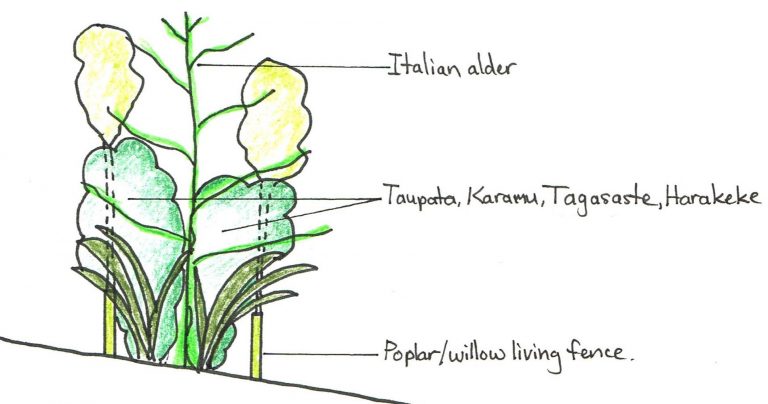

Above: The windy side of a 5 year old multi-functional, multi-layered, shelterbelt. On exposed sites, wind netting will speed up early growth of the shelterbelt.

SHELTERBELTS – so much more than just shelter from the wind. Single row, single species, trimmed shelterbelts have their place. But by thinking outside the square, we can achieve great shelter while gaining lots of other benefits too…. writes Kama Burwell.

The opportunities with shelterbelts are exciting. We can design shelterbelts so they also provide bee fodder, bird & insect habitat, rongoa/medicine, fruit, nuts, stakes, fibre for weaving, fruit tree pollination, firewood, chook food, nitrogen & phosphate fixing, animal fodder, mulch, and more.

Before we explore those exciting possibilities, let’s make sure we cover the basics of an effective shelterbelt.

A dense hedge causes the wind to bounce off it and dump over the top, causing damage to those plants we are trying to protect.

Instead, a multi-row, porous shelterbelt – shaped a bit like an aeroplane wing – will filter, absorb, and slow some of the wind, while lifting the rest harmlessly over the top of your precious fruit trees. A minimum of 3 rows is best: the shortest species on the windy side, then the tallest (mainframe) shelter tree, and then a shorter shrub on the sheltered side.

Looking from above, aim to have a U-shaped shelterbelt, open to the north for the sun. The southern part of the U will usually be thicker and have taller species, to provide extra shelter from cold southerlies. Westerlies are a key challenge in Taranaki, so the western part of the U is often thicker and taller too. Towards the northern ends of your U, taper the height of species down, to allow more winter sun in.

Choose species to suit your conditions. Some species such as pohutukawa are better suited to coastal sites, while others like cryptomeria love inland, colder sites. Others, like the ever-present harakeke and pittosporums, do well almost everywhere. Salt burn on some exposed coastal sites in South Taranaki can be a major issue and greatly reduce what can be grown. Consider how wet your ground is too – some very useful shelterbelt species like tagasaste (tree lucerne) will not tolerate a high water table.

Work out how tall you need your shelterbelt to be. Shelterbelts provide shelter for a distance that is 6-8 times the height of the shelter. So if your site is 50m wide from east to west, then your western shelterbelt needs to be about 8m tall. Choose species that only grow as tall as you need them – no point paying for hedge-trimming contractors every few years.

Consider some super-fast-growing pioneer species in your shelterbelt such as tagasaste. This tree grows metres each year, giving very quick shelter, while speeding up the growth of the main shelterbelt species. Tagasaste is short-lived, and will start to die out at 5-10 years, but by then the permanent shelter species will be up and away. Tagasaste is nitrogen fixing, provides excellent winter bee fodder, the flowers are beloved by kereru, chooks love eating its seeds, and it also makes good firewood. It really is a super tree.

On our lifestyle block in Kaimata, we designed our shelterbelts to be multi-purpose: tagasaste as above; harakeke (flax) for the tuis and to provide weaving materials; makomako (wineberry) for the bees, birds, and edible fruit; banksias for the birds; taupata (coprosma repens) for bird and chook food, willows for rooting hormone, pollinator plums (Heard & Pearnell) for the orchard, hazels for nuts and stakes, and more! The possibilities are endless…

I’ve seen shelterbelts with high value timber incorporated for a lump sum at retirement time … shelterbelts that provide an annual income from hazelnuts…. And shelterbelts providing an ongoing source of coppiced poplar logs to grow mushrooms on, plus a sheltered humid place to grow them.

If you are providing shelter for stock, there are lots of intelligent things you can do. Make your shelterbelt a fodderbelt too, with fodder trees along the edges of paddocks: stock love to nibble at taupata and karamu; harakeke is a super de-worming tonic; poplar prevents facial eczema; and tagasaste is universally loved. Stock can nibble over or through the fence at these, and you can also cut and throw branches into the paddock. During summer drought or winter feed shortages, these fodderbelts can save your bacon, not to mention your bank account.

Include deciduous alders for their nitrogen-fixing talents and the tonnes of free fertiliser their autumn leaves provide, or evergreen casuarinas which are also nitrogen-fixing. Both these varieties are also used as emergency stock fodder, and casuarina provides particularly excellent firewood.

In fact, shelterbelts in a pastoral farming situation can be doing heaps of beneficial things and even a normal boring shelterbelt that is thinking inside the square is shown to improve the profitability of farms.

So don’t be shy, think outside the square for your own (exciting) shelterbelts.

Above: A typical shelterbelt design that will work in many parts of Taranaki. Note the low-high-low shape, which is important for lifting wind while reducing dumping on the inside of the shelterbelt. Don’t use ngaio if stock can get t

Kama Burwell is an ecological engineer and landscape designer, and is part of the GreenBridge team. She “lifestyled” for 9 years on a corner of the family farm near Inglewood, before moving to a suburban garden in New Plymouth.

See other useful articles on our blog page